It’s not often that you hear Budweiser and Shakespeare mentioned in the same breath.

But according to research from Johns Hopkins University, the Bard’s deft application of storytelling techniques featured prominently in the beer company’s Super Bowl commercial.

Forget the fact that the 60-second spot (which cost north of $4 million), aired close to the end of a one-sided game that was over before halftime. The Budweiser ad scored top honours in USA Today’s Ad Meter and Hulu’s Ad Zone for being the most popular among viewers. How did it not get lost amid the tantalising displays of shiny vehicles, CGI tricks and David Beckham’s six pack?

The irresistible power of classic storytelling.

If Keith Quesenberry were a betting man, he would have cleaned up. The researcher at Johns Hopkins predicted that the Budweiser spot would be a winner after conducting a two-year analysis of 108 Super Bowl commercials. In a paper, the issue of The Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Quesenberry and research partner Michael Coolsen focused on brands’ use of specific strategies to sell products, such as featuring cute animals or sexy celebrities. But they also coded the commercials for plot development.

They found that, regardless of the content of the ad, the structure of that content predicted its success. “People are attracted to stories,” Quesenberry tells me, “because we’re social creatures and we relate to other people.”

It’s no surprise. We humans have been communicating through stories for upwards of 20,000 years, back when our flat screens were cave walls.

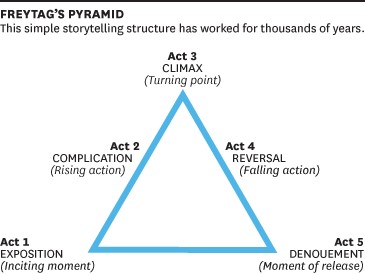

“Especially in the Super Bowl, those 30-second ads are almost like mini movies,” he says. Quesenberry found that the ads that told a more complete story using Freytag’s Pyramid — a dramatic structure that can be traced back to Aristotle, were the most popular.

Shakespeare had mastered this structure, arranging his plays in five acts to include an exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and a dénouement—or final outcome. The “Best Buds” story also uses these elements to great effect. The more of the acts each version of the ad had, the better it performed.

Storytelling evokes a strong neurological response. Neuroeconomist Paul Zak‘s research indicates that our brains produce the stress hormone cortisol during the tense moments in a story, which allows us to focus, while the cute factor of the animals releases oxytocin, the feel-good chemical that promotes connection and empathy. Other neurological research tells us that a happy ending to a story triggers the limbic system, our brain’s reward centre, to release dopamine which makes us feel more hopeful and optimistic.

In one experiment after participants watched an emotionally charged movie about a father and son, Zak asked study participants to donate money to a stranger. With both oxytocin and cortisol in play, those who had the higher amounts of oxytocin were much more likely to give money to someone they’d never met.

The implications for advertisers, who’d also like to part people from their money, are clear. But advertisers aren’t the only ones tapping into the trust-inducing power of storytelling.

Strategic storytelling has also been enlisted to change attitudes and behaviors. Two studies from the health care industry show its power: Penn State College of Medicine researchers found that medical students ‘ attitudes about dementia patients, who are perceived as difficult to treat, improved substantially after students participated in storytelling exercises that made them more sympathetic to their patients’ conditions. And a University of Massachusetts Medical School study found that a storytelling approach has also been effective in convincing populations at risk for hypertension to change their behaviour and reduce their blood pressure.

The most successful storytellers often focus listeners’ minds on a single important idea and they take no longer than a 30-second Super bowl spot to forge an emotional connection.

Widely recognised as the leading trial lawyer of his time, Moe Levine often used the “whole man” theory to successfully influence juries to empathise with his clients. In one trial, Levine was seeking compensation for a client who had lost both arms in an accident, Levine surprised the court and jury, who were accustomed to long closing arguments, by painting a brief and emotionally devastating picture and said, “As you know, about an hour ago we broke for lunch. I saw the bailiff come and take you all as a group to have lunch in the jury room. Then I saw the defence attorney, Mr. Horowitz. He and his client decided to go to lunch together. The judge and court clerk went to lunch. So, I turned to my client, Harold, and said “Why don’t you and I go to lunch together?” We went across the street to that little restaurant and had lunch. (Significant pause.) Ladies and gentlemen, I just had lunch with my client. He has no arms. He has to eat like a dog. Thank you very much”.

Levine reportedly won one of the largest settlements in the history of the state of New York.

Storytelling may seem like an old-fashioned tool, today — and it is. That’s exactly what makes it so powerful. Life happens in the narratives we tell one another. A story can go where quantitative analysis is denied admission – our hearts. Data can persuade people, but it doesn’t inspire them to act; to do that, you need to wrap your vision in a story that fires the imagination and stirs the soul.

Article: Harrison Monarth is an executive coach, and the New York Times bestselling author of The Confident Speaker and the international bestseller Executive Presence.